A Note from Our Team

I’m proud to introduce this edition of our monthly newsletter. It contains indigenous voices from across Southeast Alaska that speak with love for their wild Alaska homelands and food traditions.

You will hear from an indigenous chef, Rob Kinneen, who prompts us as Americans to consider the indigenous ground beneath our feet. I can’t think of a more important truth for us to reflect on this Indigenous Peoples’ Day and every day. As Willow and Talia of Kake make clear, indigenous food culture isn’t just located in place, but in time as well—and that time is now.

As much as our climate is changing, so too is our dialogue around food systems. These indigenous leaders are deepening the conversation and challenging us to consider the future of food. Our team believes food goes beyond the plate that it is served on and sees it as an opportunity to rebuild the connection between people and the ocean.

As you cook your fish that was harvested from the waters of Lingít Aaní, we welcome you to join us in recognizing the Lingít people with gratitude.

— Emma Bruhl, Sitka Seafood Market Communications Manager

ALASKA'S INDIGENOUS LEGACY

For many Americans, dinner time is often a multi-ethnic experience, thanks to the combined forces of global trade networks and our country’s particular history. Despite language barriers and differing traditions, food has the power to build bridges between cultures like no other force.

While flavors can be easily shared and replicated anywhere, the cultural significance of food is very much rooted in particular places, times, and people. The first humans to inhabit the lands we now call home built unique and diverse food cultures in every corner of the hemisphere, from the Arctic circle down to Tierra del Fuego. Passed down through generations, these food cultures not only offer practical information on how to prepare and cook the bounty of the land and sea, but also provide communal identity and foster individual purpose.

Sitka Seafood Market began with a mission to not just provide premium, wild-caught seafood, but to also educate members about Alaska, its communities, and the common love we all share for the sea. When you gather around the dinner table to enjoy wild-caught seafood from Alaska, consider the first fishing communities who stewarded these wild foods for generations. Their optimism in the face of external threats and model of empowerment when confronted with disheartening challenges sets an example we can all be inspired by.

Lingít Aaní

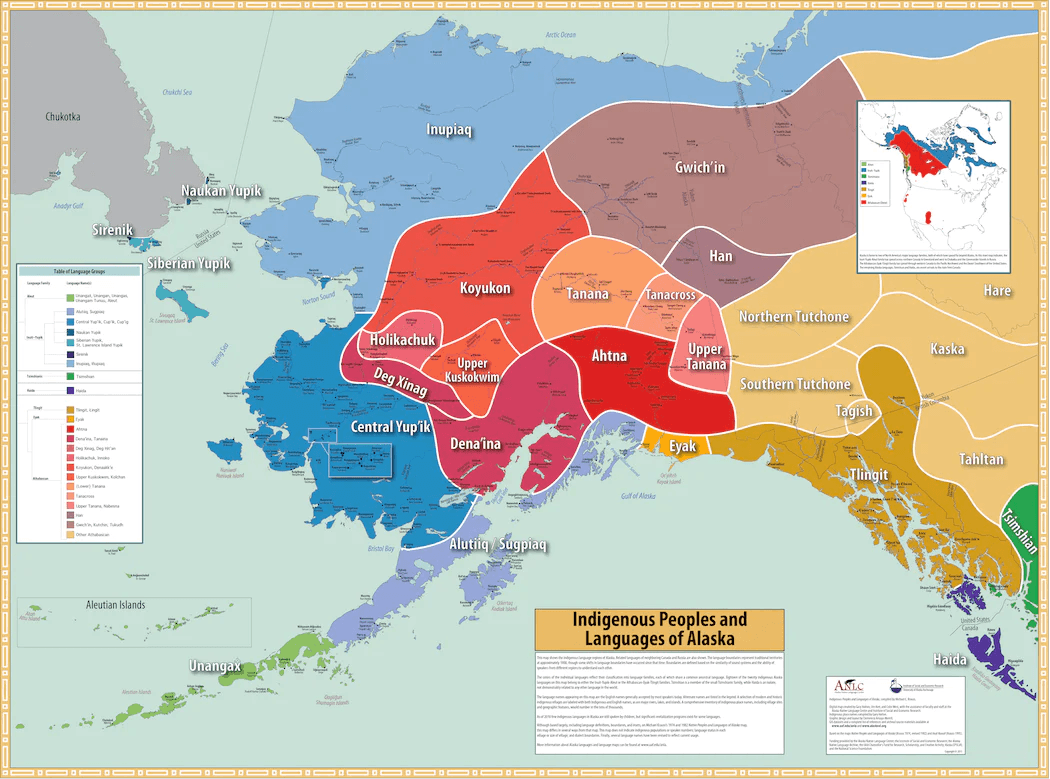

While the industrial American and colonial Russian cultures certainly left their mark on it, Sitka, Alaska, maintains its Tlingit identity. Although maps locate Sitka within the state of Alaska, you don’t have to search long before you encounter the phrase Lingít Aaní, or “land of the Tlingit”, which stretches in an arc touching most of the coast just east of the Copper River in the North sweeping down to Ketchikan in the South.

Talia Davis and Willow Jackson grew up in the village of Kake, or Keex’ Kwaan, about 50 miles east of Sitka on the coast of Kupreanof Island. They represent a generation of indigenous youth who are looking within their own culture for solutions to modern problems .

Davis, who also goes by her Tlingit name Kaajeesoox’, returned to her community when she recently felt disconnected. “I spent my first year of college studying civil engineering and quickly realized that’s not what I wanted to devote the rest of my life to,” Davis says.

She spent that summer at home in Southeast Alaska and discovered a way to merge her interests. “I began to realize that creating a career where I spent my time in the forests and on the water that raised me was a real possibility,” she says.

That year she changed her major to Fisheries and Ocean Sciences and spent the next summer as part of the Keex’ Kwaan Community Forest Partnership (KKCFP). The partnership is the product of multiple stakeholders, from the US Forest Service, the village of Kake, and environmental groups such as Ecotrust, which seek to provide a science-based and community-led solution to watershed management that is beginning to reverse years of top-down forest management.

“KKCFP provided me with the opportunity to apply my knowledge of salmon, the environment, and climate change in ways that could heal the land, water, and my community,” Davis says. This blending of the different sources of knowledge energizes Davis. “Now when I’m out in nature and find a stream I instantly start to assess it: ‘This log moved here would provide better habitat’, ‘that culvert looks like it could potentially hinder salmon passage,’ or ‘this might be my new secret fishing spot.’”

Culture Camp

Like Davis, Willow Jackson grew up in Kake and is mixing traditions to solve problems. Jackson still remembers reeling in her first king salmon when she was 10 years old. “It was a little over 20 pounds,” Jackson says. “My brother wouldn’t help me reel it in, and it took me a total of 35 minutes to reel it in by myself. I wanted to be mad at him for not helping me, but I was glad that he didn’t because after that I realized that I could fish on my own after that.”

Both Jackson and Davis grew up with culture camps, summertime community festivals where elders transmit knowledge and skills to youth on everything from how to preserve salmon for the winter to how to field-dress wild game. Jackson and Davis took these lessons to heart. “If you were to open my freezer, you would see a lot of vacuum-sealed halibut, sockeye, salmon fillets, deer, crab, and shrimp,” Jackson says. Davis and Jackson know how to preserve wild foods and they have jars of seal grease and thimbleberry jam to prove it.

Dinner with the President

Chef Rob Kinneen is no stranger to culture camps. Kinneen was born in Petersburg, Alaska, which he says looks like it belongs in Norway rather than Alaska. He didn’t have access to culture camps as a kid, but connected with his Tlingit roots through his older brother and family based in Sitka, who shared knowledge on smoking and canning salmon.

Today, Chef Kinneen shares his skills with indigenous youth throughout Alaska. He recently attended a culture camp in Bethel, Alaska, on the Kuskokwim River. Families provided ducks from a recent hunt and king salmon that Chef Kinneen prepared. “So we're out in this pretty rustic area with a fire pit. And you know, we just kind of made it work,” Kinneen says. “It was really just delightful to be out there and watching kids put down phones and play in the river.”

Chef Kinneen has spent his career advancing indigenous preparations of wild food. When President Obama visited Alaska in 2015 to highlight the effects of climate change, Chef Kinneen prepared a five-course meal for the POTUS including salmon lox and roast moose.

“There should be an indigenous food restaurant in every community across the country, because there's indigenous people everywhere across this country.”

Food Deserts

“When I was twenty, I just wanted to be a badass cook,” Kinneen says. He says his experience in rural Alaskan communities instilled in him a greater purpose. “I was working in the Matanuska Valley and this farmer said, ‘We live in a food desert.’ I was like, ‘Wait, I'm Tlingit, Native people have lived here for thousands of years and were some of the healthiest people on the planet...a food desert?!’”

The US Department of Agriculture defines a food desert as any low-income census tract where a substantial number of residents do not have easy access to a supermarket or large grocery store. Chef Kinneen says that rural Alaskan communities dependent on global trade networks do inhabit a food desert, which is why culture camps are so vital to reconnect communities to abundant wild foods. “You're talking about a gallon of milk being ten, fifteen dollars and meat being astronomically expensive,” Kinneen says.

Chef Kinneen is modest about his impact. “My platform is not that grand,” he says. He admits, “I'm not a dietitian or a doctor,” but “I'm doing events for communities, kind of teaching them and instilling confidence and pride in food.”

Efforts like his at culture camps may be paying off. In 2020, the British Medical Journal published a study documenting the first recorded decrease in the percentage of indigenous Alaskans with diabetes after decades of climbing rates.

A Brighter Future

Kinneen, Jackson, and Davis all experience their connection to wild foods and the land of Southeast Alaska in similar ways. The demands of college, careers, and the pandemic have separated all three from Alaska these past two years. “I miss how easily accessible fresh seafood is,” Jackson says.

Davis also recently moved away from Kake for the first time in her life. “I didn’t get to fish, to pick berries, or to run my smokehouse,” Davis says. “Salmon still play an integral role in my life though,” she says. “I eat it, I tan it's skins, and even now, it provides me with opportunities like this to share my love for salmon, the earth, and my people.”

Davis, Jackson, and Kinneen all expressed optimism about the future of Alaska’s indigenous communities. “The future of Kake looks bright and is in good hands,” Jackson says. “We have our tribal governments fighting to make sure our island is healthy and safe,” she says, “and we have a strong youth generation who are eager to step in and help protect Kake.” Davis agrees, “I see a future where our traditional knowledge is respected and where we can manage and steward the resources that have supported our people since time immemorial.”

For Chef Kinneen, he is empowered by other indigenous chefs promoting their cuisines throughout the United States and providing leadership for youth through culture camps. Cooking traditional stews in the bingo hall of a village only accessible by boat isn’t as glamorous as preparing a meal for the sitting President of the United States, but Chef Kinneen takes pride in those personal connections to indigenous communities. A child from a small village in the Yukon delta recently reminded Chef Kinneen about a past culture camp he participated in from 2015. “This kid was like, ‘I was there when you did that,’” Kinneen says with a chuckle.

He places himself in a growing movement to connect Americans to indigenous foods. Chef Kinneen says, “There should be an indigenous food restaurant in every community across the country, because there's indigenous people everywhere across this country.”

Learn More

Listen to our podcast Fish Talk to hear more about Alaska’s first fishermen and hear Chef Kinneen describe what it was like cooking for President Obama. You can also check out Chef Kinneen’s Fresh Alaska Cookbook for his favorite recipes from home. Chef Kinneen also recommends the North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NāTIFS) organization as a source of knowledge. NāTIFS founder Sean Sherman won a James Beard Foundation Book Award for his cookbook, The Sioux Chef's Indigenous Kitchen, and is an inspiration for Kinneen and chefs across the country seeking to “indigenize” American cuisine.