What are sockeye salmon?

Market name: Sockeye or red salmon

Common name: Sockeye salmon

Scientific name: Oncorhynchus nerka

Sockeye’s scientific name derives from the Greek ‘onco’ (meaning hooked or barb) and ‘rhyno’ (meaning nose) which describe one of salmon’s most iconic morphological changes: male's pronouncedly “hooked” or enlarged nose, as well as a curved and snaggly-toothed lower jaw called a “kype" that develops when they swim upstream to spawn and later die.

The reason behind this morphological change before spawning is a matter of debate, but anyone who lives close to a salmon spawning stream can see that a salmon’s teeth are used in fairly aggressive altercations during the spawning season. Male salmon often fight for female attention and females similarly defend their “redd” or the nest where they lay their roe.

Fun Fact: Some paleontologists point to this behavior as evidence that the prehistoric “saber-toothed salmon” or “spiked-toothed salmon” likely used their sharp, almost tusk-like teeth to defend their territory in a manner similar to today’s salmon.

Salmon also change colors when they prepare to spawn. The colors and markings differ depending on their species. Sockeye typically turn a bright red color with an olive green head. The males also develop a pronounced hump on their back. In the film below you can see the different spawning colors of keta, pink, and sockeye salmon (around 23 minutes into the film).

Like all five species of Alaska salmon, sockeye are a wild species of anadromous semelparous fish which is the scientific way of saying that they transition between freshwater and saltwater during their lifecycle and spawn (lay eggs) only once in their lifetime before dying in their natal stream.

Something that is particular to the life history of sockeye salmon is that they spend 1 to 4 years growing in lakes prior to migrating to the ocean where they live for typically 3 years (which is more than pink salmon, but less than king salmon) in the salty ocean before returning to their natal freshwater stream to swim up river, spawn, and die.

Why are sockeye salmon red?

Besides just turning red when they swim upstream to spawn, sockeye salmon are known as “red salmon” due to their distinctively deep, red-colored flesh which is high in richly-flavored natural oils.

“Sockeye salmon have more of the antioxidant astaxanthin than any other salmon.”

Sockeye salmon’s striking color is due to their natural diet of zooplankton — tiny marine animals such as krill — which have a carotenoid pigment. Carotenoids are the same pigments that give a ripe tomato its bright red-orange hue; the type of carotenoid found in salmon is called astaxanthin, which is an antioxidant.

Are sockeye salmon healthy to eat?

Yes! Not only do sockeye salmon have the highest amount of antioxidants, but they also deliver the highest protein and vitamin D content per serving of all five species of salmon making sockeye a very healthy, all-natural, wild food. What’s more, they’re a good source of vitamin B-12 and healthy fats like omega-3 fatty acids.

How do Alaska’s small-boat fishermen catch sockeye?

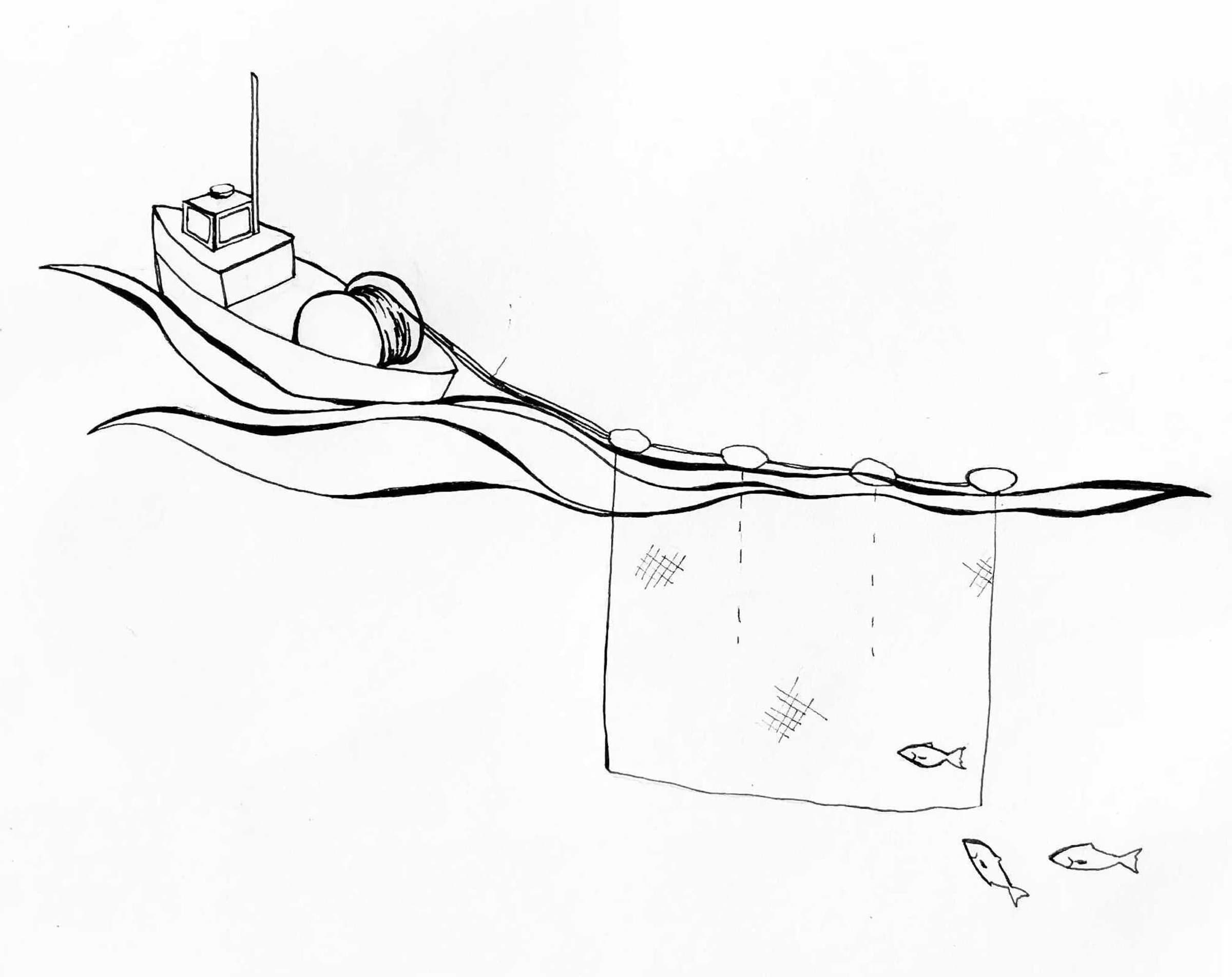

Alaska sockeye are harvested commercially in net fisheries such as drift gillnets. Gillnet fishing is similar to a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in that the main ingredients are right there in the name. Gillnets are nets that catch fish by the gills.

Fishermen set out a large rectangular net that hangs down like a curtain from the surface of the water where the net is attached to a line of floats. While the net “soaks” for about an hour, sockeye salmon try to swim through the curtain. If the salmon are too small to harvest, they swim right through, and if they’re too large to harvest, they can’t enter far enough into the mesh to be caught. But if they are the correct size, their gills are caught in the net mesh. Mesh size restrictions also limit the catch of other non-target species known as “bycatch.”

The fish that are caught are then hauled in to the boat so fishermen can untangle each slippery fish before picking them out of the net one by one and immediately bleeding and chilling them.

How do I know my sockeye is good quality?

Know the source of your sockeye: Who caught it, how was it caught, and how was it handled? Sourcing from small-volume fisheries is important — fewer fish arriving at the processor all at once means that each fish is filleted and reaches the freezer more quickly, locking in a superior taste and texture.

Equally important is finding fish that was harvested by fishermen who understand the importance of soft handling, swift bleeding, and immediate chilling. You can see in the video above, taken on a drift gillnet vessel on the Copper River by Sitka Seafood Market Co-Founder Marsh Skeele, that every fish is carefully picked and quickly bled without even touching the deck.

Where are sockeye caught?

Sockeye salmon are caught in communities across Alaska including the Bering Sea, the Gulf of Alaska, and the Southeast region. Some of the most famous sockeye fisheries include the Bristol Bay fishery, as well as King Cove, Copper River, upper Lynn Canal, Prince William Sound, and upper Cook Inlet fisheries.

Each region of Alaska’s sockeye fisheries boasts different strengths — the Chilkoot and Chilkat sockeye runs near Haines, Alaska, are the largest in the Southeast region, while the King Cove harvest is one of the earliest of the season. Regardless of the region, all Alaska sockeye fisheries are managed with the same commitment to sustainability by the state which is widely regarded as setting the standard for responsible fisheries management.

The Alaska Department of Fish and Game employs biologists who use tools such as in-river sonar, aerial surveys, and harvest data to make decisions about which days the fishery is open for commercial harvest depending on what they see in real-time.

Since the ocean is constantly changing, there is variability in how many fish return to spawn each year. That’s why managers set “escapement goals” based on what scientists are observing in the field to ensure that there are enough salmon safely returning to spawn to support the sustainability of Alaska’s sockeye runs for years to come.