Wild Alaska salmon are at the core of what we do at Sitka Seafood Market. They have nourished communities throughout the Pacific for millennia. They connect marine and terrestrial habitats. They provide billions of dollars of economic development for Alaska’s shoreline communities.

Like all wildlife, they are also under the gun. Urban sprawl, dams, resource extraction, and climate change all threaten the viability of salmon runs. The threats are many and complex, but the bottom line is if humans replace salmon habitat with mines and malls, we shouldn’t be surprised to see the fish abandon rivers and streams they have called home for millions of years.

Wild Salmon Habitat is Key

The bad news piles up every day for wild salmon in the lower 48. In July, California officials warned that heat waves threatened a “near-complete loss” of juvenile king salmon in the Sacramento River. Along the Snake River in Washington State, wildlife managers have taken to scooping sockeye salmon out of the water and trucking them hundreds of miles to central Idaho to give them a better chance of surviving the heat.

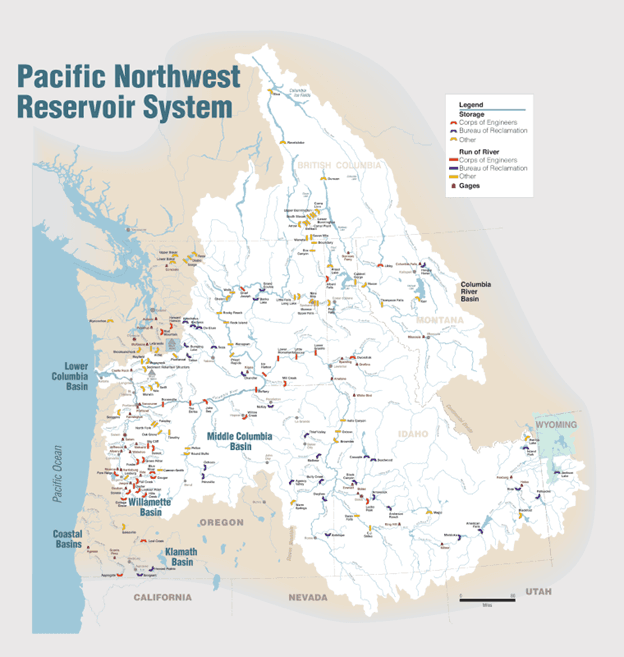

Wild salmon in Alaska have their share of perils, but they have one major advantage over their cousins to the south: intact habitat. While the Columbia River watershed is home to over 60 dams that block salmon runs, you are more likely to encounter beaver or ice dams on Alaska’s rivers. The Yukon River sports a single dam over 1,000 miles upstream in Whitehorse, Canada.

Alaska’s Sockeye Salmon Gold Rush

All this habitat makes for record-breaking fish runs. In July, fishermen in Bristol Bay caught over 2 million sockeye salmon a day, far exceeding a 5-year average thanks to record sockeye stocks. Those stocks are there because the community has fiercely fought against threats to the habitat. Twenty years ago, that threat was in the form of offshore hydrocarbon wells. This past decade, the proposed Pebble Mine loomed until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rejected a crucial permit for the mine.

Decision makers aren’t saving Alaska’s salmon habitat out of the goodness of their hearts, however. A recent report by McKinley Research found that the salmon run in Bristol Bay created in excess of $2.2 billion dollars of economic benefits per year. Beyond that, the salmon run accounts for 29% of the subsistence harvest of salmon in the entire state. By creating over 15,000 jobs and directly feeding hundreds of Alaskans, the value of the Bristol Bay salmon run dwarfs the economic impact of any proposed mineral mine, petroleum well, or timber harvest.

To Save Wild Salmon, Eat Wild Salmon

What can you do to protect salmon habitat? “Eat fish. Eat wild fish,” says Dr. Daniel Schindler, professor of biology at Washington University’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. Dr. Schindler suggests worried consumers should vote with their dollars.

“I meet people all the time who say, ‘well, I’m not going to eat that fish, the thing’s endangered. By eating it I’m just going to kill one more fish’” Dr. Schindler says. “It’s actually the exact opposite.” Because the state of Alaska limits the commercial catch to a level below what nature will reproduce the next year, wild salmon from the state are the closest thing we have to a renewable resource in today’s marketplace.

Holding value in the human world is critical to the survival of species. In his recent book, The Anthropocene Reviewed, author John Green writes that, for wild species, “the single most important determinant of survival is whether their existence is useful to humans.”

A Future for Wild Salmon

Regardless of whether you agree with Green, the data on our relationship to the natural world is stunning. The combined weight, or biomass, of our species is currently about 385 million tons. The biomass of our livestock is about 800 million tons. Combined, our species and our food weigh over a billion tons. That number is impossible to imagine except through comparison. Wild mammals and birds, everything from tigers to penguins, account for less than 100 million tons.

Wild salmon and other fish are winning the biomass game, weighing about six times the combined amount of humans and our livestock. But the future of the sea is likely to mirror the story on land in the recent past.

The natural world has intrinsic value regardless of whether humans find it useful or not. But as the human species extends its powers to the deepest reaches of the sea and the limits of space, we should take a lesson from the past. Whether we like it or not, the plants and animals that appear on our dinner plates are far more likely to survive into the future than their less tasty neighbors. That is why eating wild salmon is one of the best ways you can protect them.