How we fish matters.

It shapes the quality of what ends up on your plate, the health of our oceans, and the future of wild seafood. In Alaska, where nature still writes the rules, fishermen rely on gear that reflects respect for the marine ecosystem and generations of hard-earned wisdom. From the time-tested longline to the modern-day pot, each method has a story — not just of how it works, but why it’s chosen. This post dives into the gear that brings halibut, sablefish, spot prawns, and crab from Alaska’s wild waters to your table — and how these fishing methods take care of your catch and the ocean.

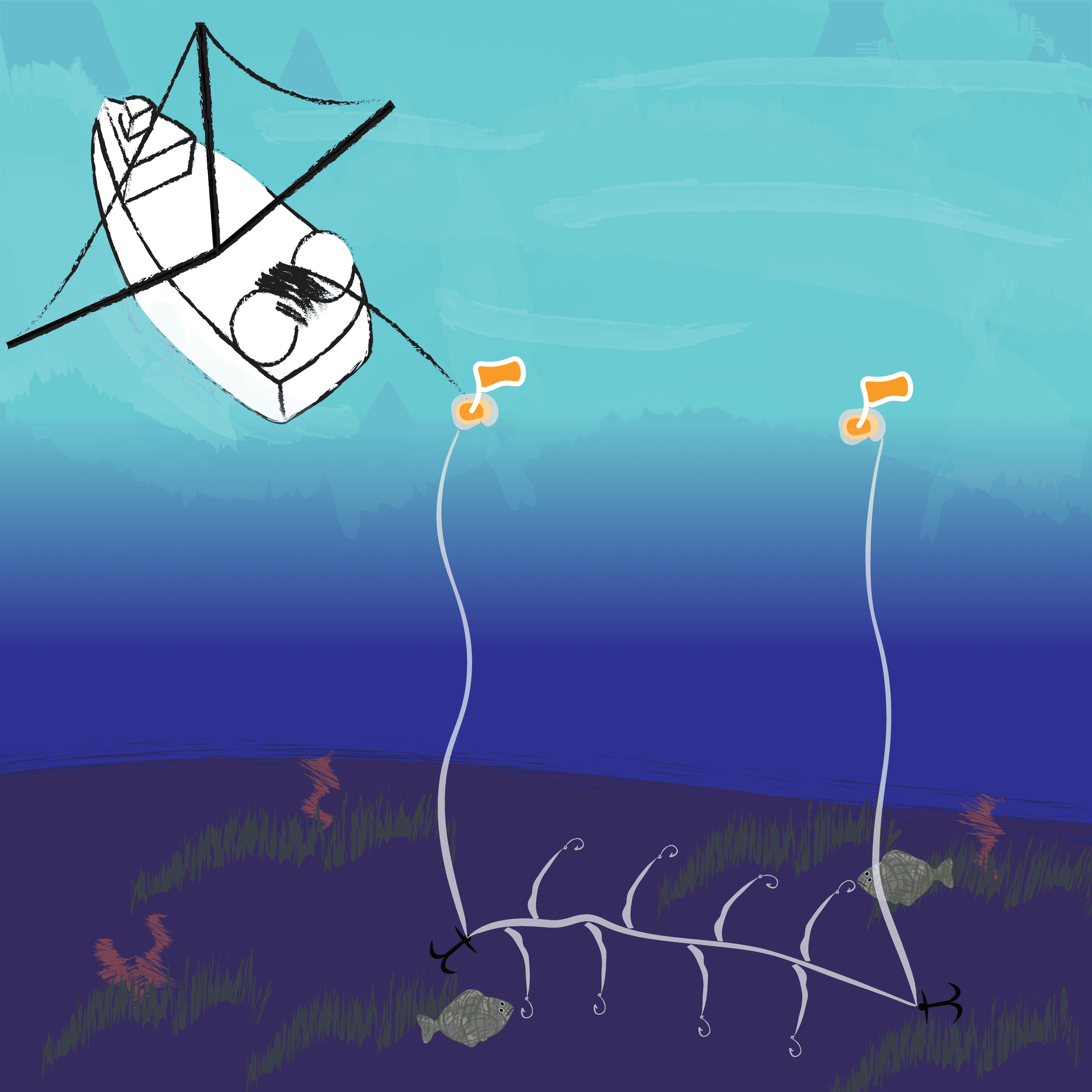

Catching Alaska halibut commercially relies primarily on one gear type: the longline. A longline uses a main fishing line that lies along the ocean bottom, with numerous shorter lines, called gangions, bearing hooks attached off to the sides. Fishermen bait the hooks with pink salmon or herring and drop the lines — often many miles long — along the bottom. The hooks have a curved tip that protects fishermen from being hooked, improves bait retention, and holds halibut longer than traditional J-shaped hooks. These “circle” hooks weren’t used in Alaska until the mid-1980s, and they dramatically improved catch rates. The design is similar to the hooks coastal Native peoples used for thousands of years; it simply took time for that traditional wisdom to pass into commercial fisheries.

Longlining has been around for thousands of years. Since the first native peoples crafted lines from spruce root fibers and tracked the seasonal migration of halibut, fishing the ocean’s bottom has depended on this method. Sitka spruce roots are strong and flexible, making them ideal for fishing lines. As halibut move into shallower water in summer to prey on salmon and herring, longlines are set and halibut become the targeted catch. In modern times, the technology hasn’t changed much, aside from longer and stronger lines and hydraulic winches to haul them in.

Once a longliner lays down their baited hooks on the ocean bottom, they may wait from 3 to 24 hours. Some areas have an active bottom with abundant sand fleas or isopods that will attack and kill fish on the lines, so in those areas the gear soaks for only a few hours. Other bottoms are rocky and shallow, with a lower risk of sand fleas harming the fish. After the gear has spent an appropriate time on the bottom, it is retrieved and hauled back in. This hook-and-line method allows unwanted species to be released alive, returning to their bottom habitat. The types of ocean bottom support vastly different fish species; depth and season also influence which species, including halibut, can be caught. Some of the interesting fish we catch while longlining are lingcod, China rockfish, red Irish lord, and ratfish.

This selective fishing method is not only more sustainable, it also gives fishermen time to handle their catch properly. Halibut, when landed, are immediately bled, cleaned, and packed in ice. This step is crucial to honor the fish by ensuring the best quality. Bleeding preserves the ivory-white flesh, and chilling helps maintain the firm texture we love in halibut.

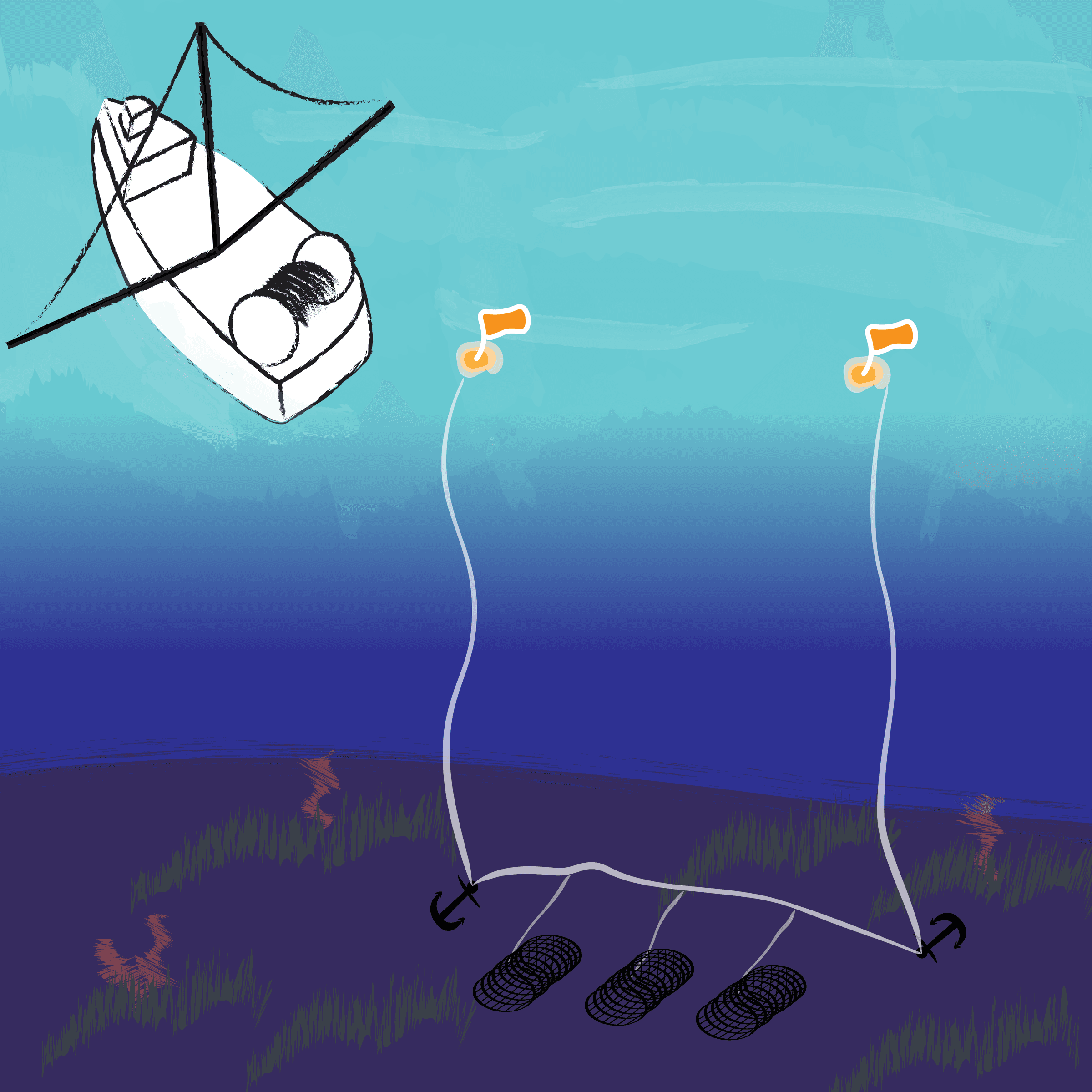

The same gear type is also used to catch another favorite: sablefish (a.k.a. black cod). These oily, omega-3-packed fish live at the edge of the continental shelf, at depths over 2,000 feet. The extreme depth means high pressure, and sablefish have a unique adaptation to survive there. Their fat content helps regulate buoyancy and makes them especially tasty. Unfortunately, other predators — namely sperm whales — also prey on oily fish. While longlines are still used to catch sablefish in many areas, some regions experience intense sperm whale predation, forcing fishermen to leave the area. Each year, more sperm whales learn to exploit longliners, prompting changes. Some fleets began experimenting with pots or traps for sablefish. This approach has grown in popularity because it reduces fish losses to whales and offers additional benefits: less crew time spent baiting gear (a major portion of effort on sablefish longliners) and reduced bycatch, since rockfish don’t swim into pots as readily as sablefish. Today, over 80% of Alaska’s sablefish harvest is in pots, and fishermen aren’t looking back.

Pots, or “traps” as they are sometimes called, are highly effective for catching fish and are also among the few methods for harvesting wild shellfish.

Our Alaska spot prawns live in deep, rocky terrain, and pots are the most sustainable way to harvest them. Using pots allows fishermen to release different fish and unwanted crabs and snails alive, and to keep their catch in live tanks on deck. For spot prawns specifically, this is important because if they die with their heads attached, the meat becomes soft very quickly. Fishermen keep them alive on deck with circulating seawater and then remove their heads while alive to keep the meat in prime condition. It may sound inhumane, but the process is rapid and is the only way to ensure their quality.

Dungeness crab are also harvested in pots around Alaska, but they are kept alive in tanks to be brought to town for processing. If they die before cooking or shucking, the meat can spoil, so they are kept alive, cooked, and then broken down into the leg clusters we enjoy. Crabbers target inland sandy and muddy areas with their pots and experience very little bycatch. Most bycatch in those regions consists of starfish, which are returned to the sea alive and have largely recovered from the major die-off that occurred from 2014 to 2017.

We’re not just fishing for halibut or sablefish — we’re fishing for a future. And every time we set a line or haul a pot, we’re reminded that if we take care of the ocean, she’ll keep taking care of us.