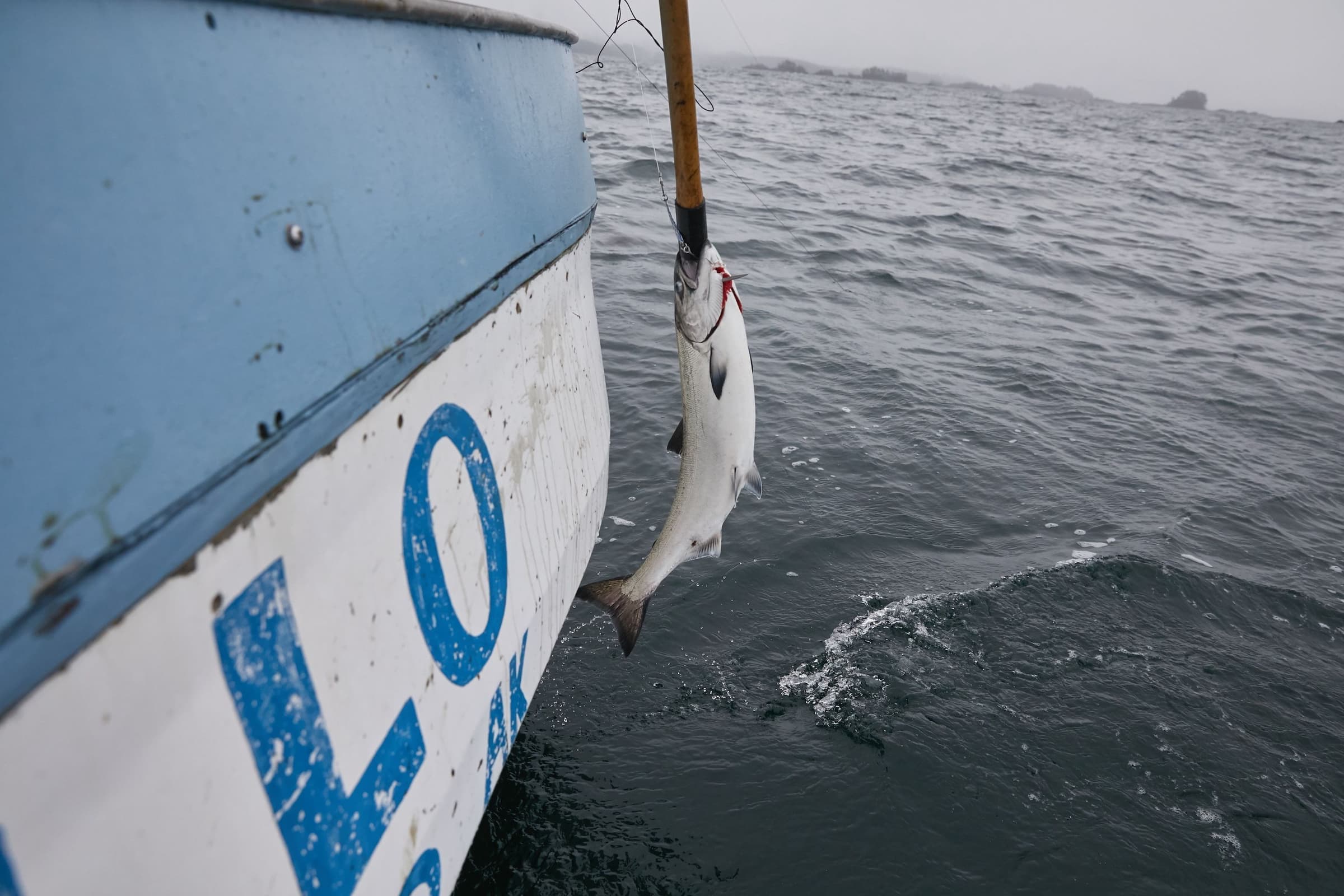

King salmon are essential to the survival of Southeast Alaska’s troll fleet, and access to this historic fishery has faced increasing challenges. Unlike coho or sockeye — which grow quickly and return to spawn after a single season at sea — king salmon, or chinook, spend multiple years maturing in the ocean. That means full-sized kings are swimming in the waters around Southeast Alaska year-round.

In the dark winter months, those king salmon become especially important. Their year-round presence makes a winter troll fishery possible in Sitka Sound and across Southeast Alaska. These seasonal openings give hook-and-line trollers a chance to keep fishing through the off-season, helping them stay afloat financially and making up for those tougher, less predictable summer runs.

If your engine breaks down during the summer king salmon opener or you pick the wrong spot and miss the hot bite, your season might be in jeopardy. But for many fishermen, winter openings offer a second chance — even as storms pound Alaska’s rugged coastline and make fishing tough, they still provide an opportunity to salvage the year.

It’s not just hook-and-line trollers who love catching king salmon. Sport fishermen visiting Sitka often target kings for the same reasons you do. Local Alaskans also invest heavily to prep their boats for a chance to fish for these prized salmon. Each gear group — charter or sport, local subsistence, and commercial — has its own quota within the total allowable catch. For years, this system has helped manage the fishery sustainably. But as tourism has grown, the sport fleet has expanded rapidly. In the last two seasons, the sport fleet exceeded their quota, and there were no mechanisms in place to slow them down. This resulted in them catching more than their allocation, leading to early shutdowns for the commercial fleet and local subsistence fishermen.

This hurt the troll fleet, processors, and markets like ours that rely on those kings. Tensions began to rise on the Sitka docks as the commercial and subsistence sectors faced shutdowns with no recourse. Fortunately, Alaska’s robust fisheries management system stepped in to address the issue.

This spring, the Alaska Board of Fish met, and one of the proposals discussed was the introduction of in-season management for sport-caught king salmon. Under this system, allocations to each group are decided by a committee after hearing testimony from all sides.

Sport fishermen argued that they needed kings to operate their businesses, while the troll fleet insisted that the only solution was for management to hold each gear group accountable. After days of testimony, the board reached a resolution. Commercial fishermen agreed to give up 3% of their quota to establish in-season management. This means that when the sport fleet hits their quota, rather than shutting down all gear groups, only the sport fleet will be closed for the season on kings. Trollers and subsistence users will still be allowed to catch their fish and continue their seasons. Although the commercial troll fleet wasn’t happy to give up fish, being able to fish for kings in August is a significant win. That is Alaska’s fisheries management at work — many hardworking people using their energy to support sustainable harvests for all.

Speaking of sustainable fisheries management, I often get asked, “How are king salmon doing?” The answer is complicated due to their wide range, but it’s quite interesting how Alaska’s most valuable salmon are managed.

Outside of Sitka and in the Gulf of Alaska, king salmon spend their lives growing fat on the abundant herring and needlefish that habitat provides. Many of these salmon didn’t originate here; they may have started their lives in a river in Oregon or British Columbia, but they spend their adult years in the Gulf of Alaska. If they’re from one of the rivers within their roughly 2,000-mile range of the North Pacific but spend their adult lives in the Gulf of Alaska, who gets to catch them?

King salmon are managed under the Pacific Salmon Treaty. This treaty involves cooperation between the four Pacific U.S. states and British Columbia to promote shared conservation of salmon stocks. The Pacific Salmon Commission, composed of representatives from both the U.S. and Canada, oversees decisions about how many king salmon can be caught, and monitors the salmon populations. The treaty aims to share the benefits fairly between the two countries and to protect Chinook salmon for future generations. They use fish counts across hundreds of rivers to understand how many salmon are returning, which helps set quotas. Then, the state of Alaska manages the quotas in-season to prevent overharvesting.

While complex, this system demonstrates how well-managed fisheries and protected habitats can sustain salmon populations year after year.

This means that each year, based on scientific assessments of salmon populations, quotas are set to allow responsible harvests. The remaining "pie" of king salmon harvest is then divided among the states and British Columbia. Though complicated, this process is necessary to address the challenges of managing the complex and international migration and harvest patterns of salmon.