We take great effort and pride in sourcing seafood for our members that meets our sourcing standards. We chose wild Alaska sockeye salmon landed in King Cove, Alaska, because of the high-quality, low-impact gillnet gear, small-boat harvest, and relatively early timing compared to other wild sockeye runs in Alaska.

King Cove’s gillnet fishermen are able to fish for sockeye early in June, which is earlier than many other parts of Alaska, such as the Bristol Bay fishery, where fishing begins in late June and early July. This early start allows us to have sockeye salmon shipped in time to make it into our members’ September shares. Additionally, this run of early sockeye is also known to produce particularly high-quality fish because it is a small volume fishery—fewer fish arriving at the processor all at once means that each fillet reaches the freezer more quickly, locking in that superior taste and texture.

These sockeye were caught during what is called an “opener,” meaning that there are limited hours when certain fishing grounds are open to be fished. When the grounds are open, fish are harvested using gillnets by small-boat fishermen. Each fish is pulled by hand from the fisherman’s net and tendered back to King Cove to be quickly processed and blast frozen by the team at Peter Pan Seafood. Rich Wolverton, of Peter Pan’s sales team, explains that processing the fish locally “allows us the freshest possible fish to go to Sitka [Seafood Market].”

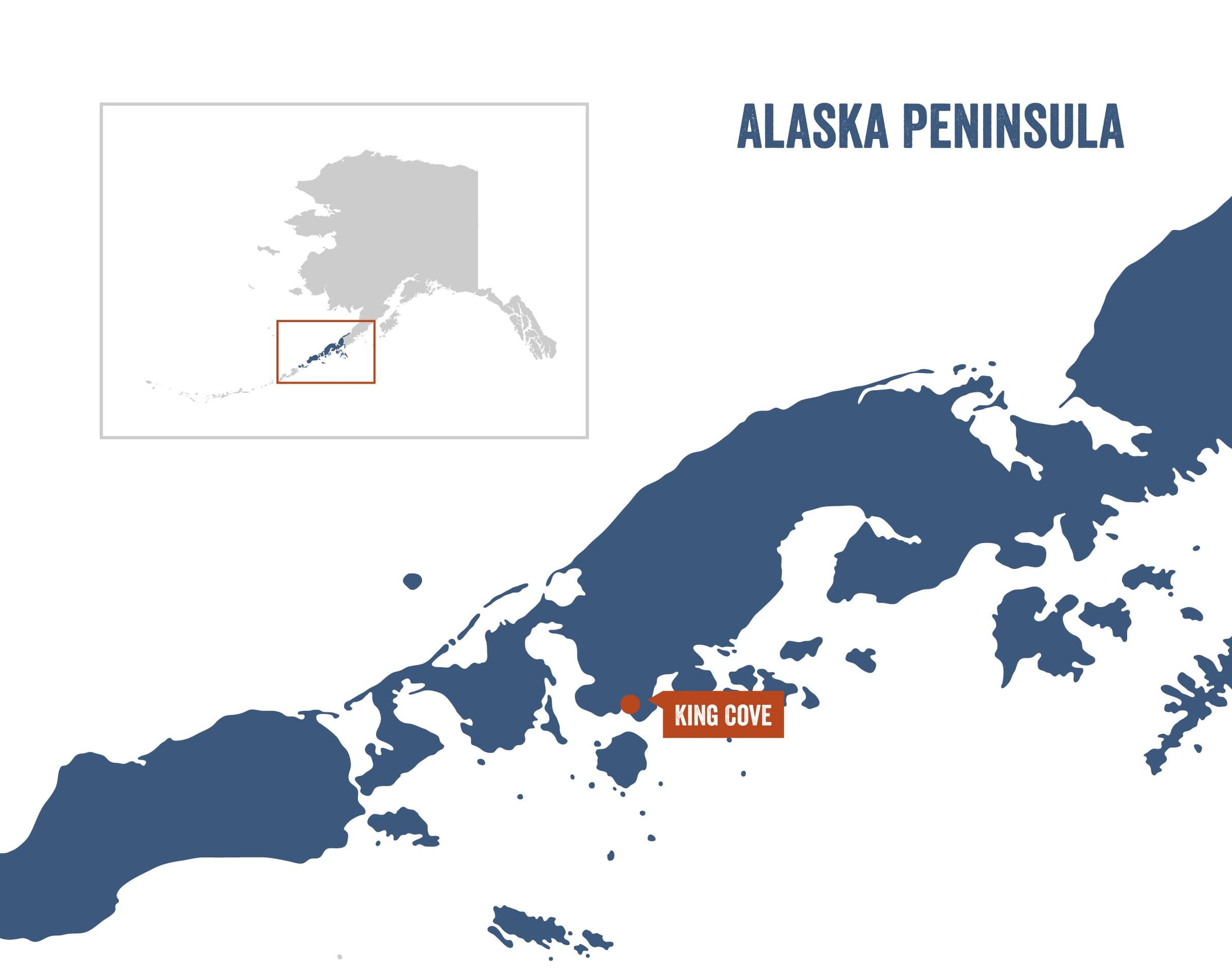

Peter Pan Seafood owns a seafood processor located in King Cove, a small town of around 1,000 year-round residents on the Pacific Ocean side of the Alaska Peninsula. Locals there primarily make their living harvesting and processing seafood. In 1911, Pacific American Fisheries established a processing and canning facility in an area called Agdaaĝux̂ by the indigenous Unangan (Aleut) people. A handful of both indigenous and non-indigenous families moved to work at the cannery and the town of King Cove was conceived. That same fish processing facility has continued to be the primary employer in King Cove for over a hundred years, and today is called Peter Pan Seafood.

Peter Pan Seafood brings money into the small community, but just as importantly, according to Matt Frazier of PPS, is the support the company offers. “I think the number one thing to assess is how [the fishermen] are getting paid, but I think it’s also how a company takes care of them.” Matt says that PPS works hard to produce sustainable seafood that benefits both the ocean and the people. This dual approach resonates with our values-driven mission at Sitka Seafood Market.

Peter Pan Seafood not only works in certified sustainable fisheries but also focuses on their local impact. Matt says that the extremely remote nature of their work “helps, specifically the villages in the state of Alaska.” He goes on, “We take great pride in our fleet, and provide the best service and support possible to our fishermen. And if we can support the people that are catching the fish—and do that all the way through to our customer—everyone wins.”

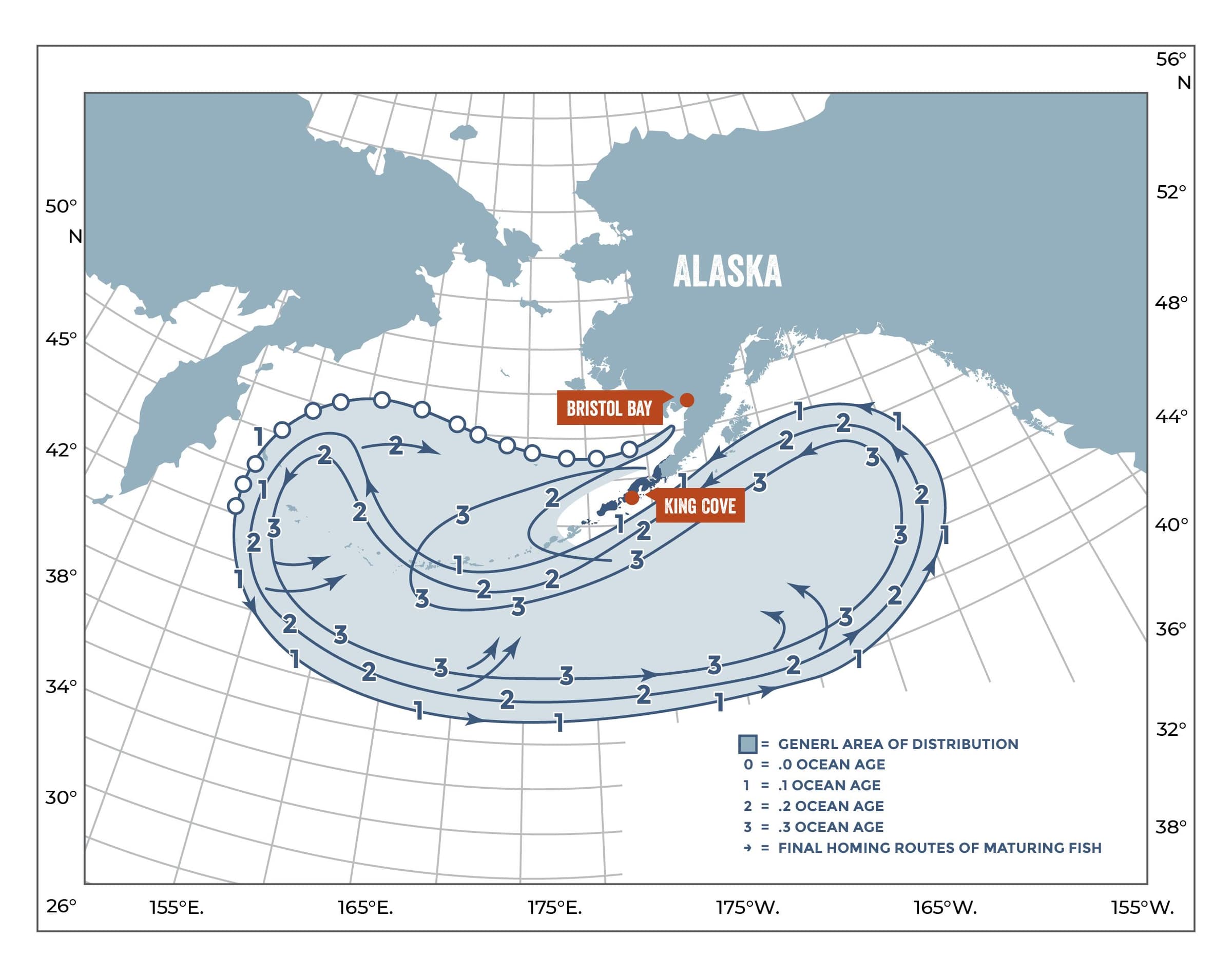

Indeed, this summer was a banner season across Alaska’s Southwest region and famously in Bristol Bay. King Cove is located around 300 miles away from the bay; however, the link between King Cove sockeye and Bristol Bay sockeye is much closer than that distance may imply. Specifically, the majority of the fish caught in the waters near King Cove actually started their life in Bristol Bay; They were spawned in the bay’s prolific river systems and are called “intercept fish” since they were intercepted while traveling north towards their natal streams (birth streams) to spawn.

When sockeye salmon leave their natal stream and head out into the open ocean, they travel vast distances. In fact, they go almost as far west as Russia before returning to the Gulf of Alaska, at which point they can navigate through the islands of the Alaska Peninsula where the gillnet sockeye fishery around King Cove is located.

The multifaceted role of seafood in the community as both a food and a commodity illustrates the importance of ensuring the continued health of wild salmon stocks in the future. That’s why the Alaska Department of Fish and Game conducts studies in the field to closely track both where salmon originate and where they go during their life in the open ocean. During an opener, scientists work at camps located in remote salmon spawning areas taking genetic samples to understand where a specific population of fish spawned.

The fishermen themselves also contribute crucial data. Fisherman Nora Skeele, sister of Sitka Seafood Market Co-Founder and Vice President Marsh Skeele, wrote about this in her article for the National Fisherman last month saying, “After our catch was weighed, the tenders submitted paperwork accounting for every fish harvested, including their precise location—data shared in real time with fishery biologists ...”. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game uses that information to calculate how many fish are sustainable for subsistence, commercial, and sport fishermen to catch so that plenty of salmon are allowed to return to their natal streams to spawn. It also allows biologists to ensure that streams are not overcrowded, which can reduce the number of fish that can spawn and contribute to the next generation of salmon.

These longtime series data sets are important for scientists and fishery managers to be able to evaluate the current health of certain fisheries versus how these fisheries compare to the previous year’s performance. In this way, fishermen, scientists, and the fish themselves exist in a dynamic, interdependent system.

For instance, the Bristol Bay fishery had an unprecedented season this year with the most sockeye salmon ever to return to the region since the fishery started back in 1883. Headlines called it “record-breaking” and the Anchorage Daily News exclaimed, “Bristol Bay commercial sockeye salmon catch shatters record.”

Avid sockeye enthusiasts are likely familiar with Bristol Bay due to its prolific sockeye runs as well as the ongoing campaign to protect the bay against proposed mining such as the Pebble Mine Project—a massive open pit mine intended to extract copper, gold, and molybdenum at the headwaters of the world’s largest run of wild sockeye.

Seeing this year’s abundant wild salmon run across Southwest Alaska, including King Cove, is a timely reminder of why it’s imperative that these critical salmon spawning habitats are able to remain healthy and unpolluted for future generations. It prompted Nora Skeele to wonder, “Do you think this huge show of salmon will wake people up and remind them this area is worth protecting from mining?”

This year, salmon flooded our rivers with nutrients and many hearts with relief. Their return indicates the renewal of another quiet cycle of resilience. In the face of external threats and our changing oceans, salmon continue to circle back to their natal streams and with them we circle another year—thrumming with energy and the work that slowly winds down in September when we pause to watch fish swim upriver to spawn.

As you enjoy your fish, we invite you to reflect on that energy—a continual chain that extends from your plate all the way to the smack of the fish’s tail propelling itself through the water. From the strain of the fisherman’s back as she pulls in the fish, to the concentration of the filleters guiding their knives, from the hands of our team members curating your box of fish, to those of your mailman—each spurt of energy offers an opportunity for gratitude, an opportunity to take that energy, let it nourish us, and then cycle it back out into the world as our own offering in this next cycle of our lives.