Celebrating the Bounty

Our offerings have grown to include a rich diversity of sea life over the past 11 years, but every summer wild Pacific salmon return us to our roots. As we welcome the return of salmon to our subscription boxes, we wanted to prepare you with a crash course on these amazing (and delicious) fish.

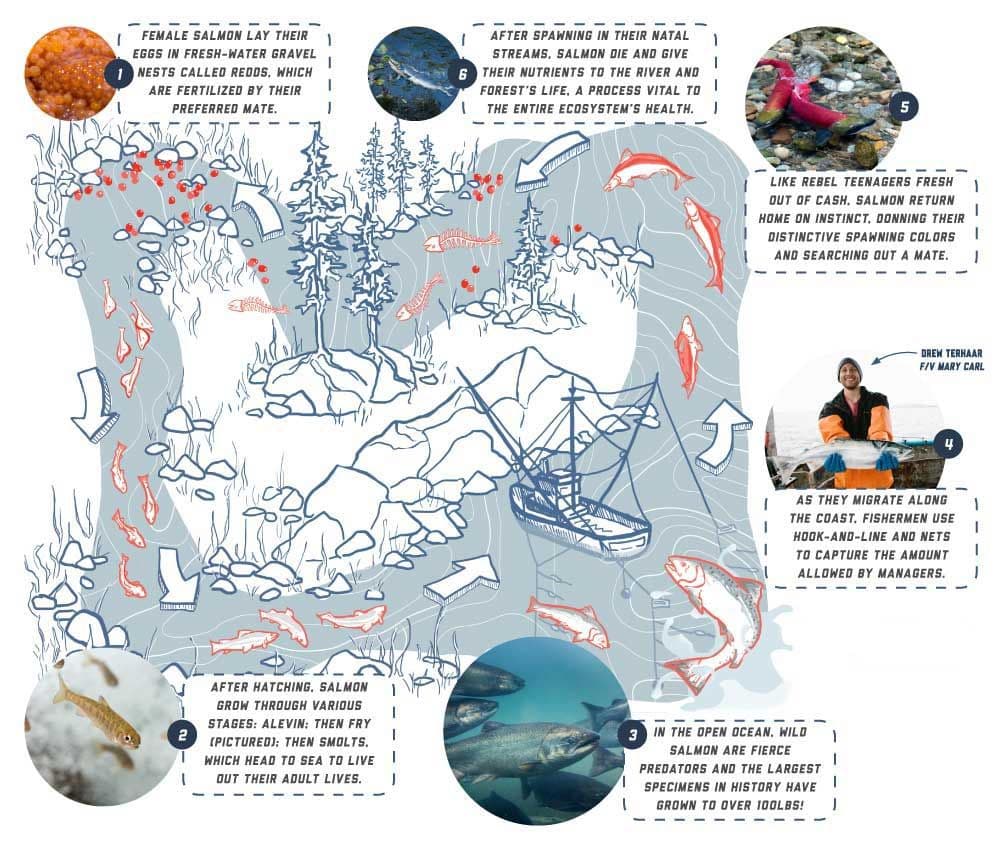

Salmon are survivors and have developed unique traits to thrive in diverse environments. Biologists are still reconstructing the genetic history of salmon, but we do know that salmonids diverged from other finned fish sometime when dinosaurs still walked the earth. They distinguished themselves through two iconic traits: anadromy and semelparity. Anadromous fish spawn in fresh waters, spend their adult life in the sea, and return to their natal streams to spawn. Semelparous fish die shortly after reproducing.

Although there are notable exceptions within the salmon family, anadromy allows salmon to access diverse habitats, while semelparity limits the competition between generations for the same resources.

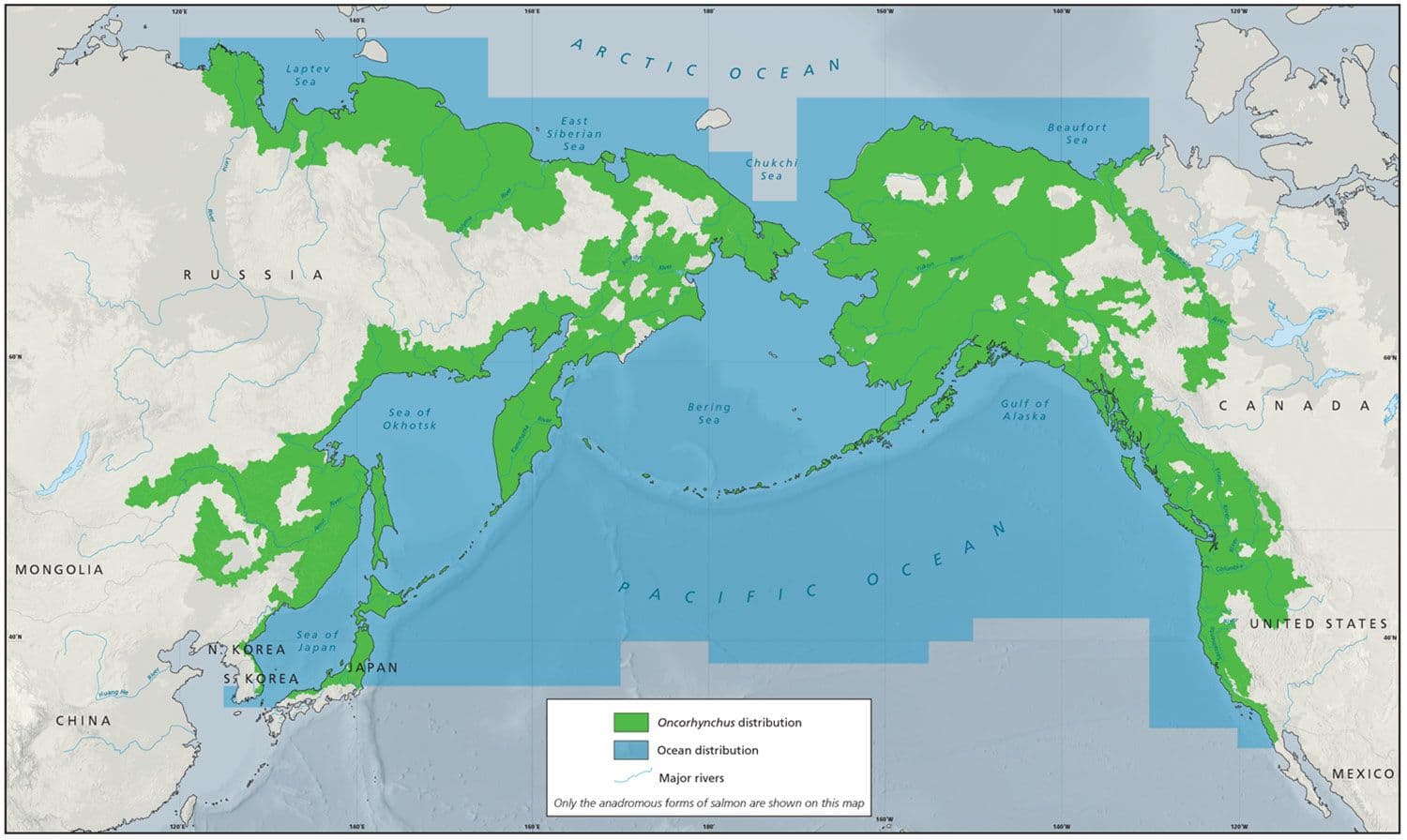

These two strategies have profound impacts on both ecology and human culture. As human populations migrated from East Asia to North America, they would have been familiar with most of the salmon species they found. Pacific salmon populations inhabited environments in a wide arc across the North Pacific, from the Korean peninsula and Japan in the west, to the Arctic Circle in Siberia and Alaska in the north, and down the coast in North America all the way to the present day border of Mexico. Their anadromous habit pushed salmon 1,000 miles or more upstream into the headwaters of mighty rivers like the Yukon, Mackenzie, Fraser, and Columbia.

Indigenous communities in the Pacific Northwest have celebrated the first salmon of the season for generations and rely on fish camps in the summer for subsistence. Salmon not only set the seasonal subsistence schedule for indigenous communities, but they also created valuable trade networks that stitched communities together — similar to the way the fish connected terrestrial and marine environments. The bonanza of salmon that surged through bays, estuaries, and river systems every summer required new technologies to preserve their bounty through the long winter months. Late season runs could be frozen and stored in snow, but the summer fish had to be dried, salted, jarred, or smoked to preserve their nutritional value until the next year’s catch.

Humans are relative latecomers to the ecosystems tied together by salmon. Wild salmon feed (and feed on) a rich variety of animals and plants throughout their life cycles. From the moment they begin their lives as fertilized eggs, salmon are gobbled up by birds and other fish. As they pass through dangerous and awkward adolescence and migrate to the open ocean, salmon feed killer whales, seals, sea lions, and you! Throughout their lives they devour larvae, insects, worms, tiny crustaceans such as krill, and just about anything smaller than they are that wiggles by. The lucky adults who survive and return to their natal streams have to run a gauntlet of rapids often guarded by hungry bears.

Salmon are critical to the terrestrial environments they visit as they spawn because they return energy from the sea in the form of their bodies that feed a host of animals and plants.

Salmon are responsible for as much as 25% of the nitrogen that nourishes riverside trees such as Sitka spruce.

Some biologists are looking at the potential to reconstruct the relative size of past salmon runs by studying the thickness of tree rings!

The culinary applications of salmon are as diverse as the species themselves. Thankfully our culinary director, Grace Parisi, has prepared culinary profiles for each of the four species we offer. Keta, the mildest and leanest of the four (about 4 grams fat per 4 ounces), is a good choice for those of us who are salmon-shy. With firm, pale-pink flesh, Grace says “it’s practically a blank canvas for all types of flavors, particularly soy-based marinades, spice rubs, and pastes, especially with a little added fat.” Keta is versatile enough for loads of preparations, from curing, to grilling, to batter-frying, and turning into burgers.

Sockeye is about 2 times fattier and about 10 times more flavorful than keta. “If this is your entrée into the world of salmon, be ready — it packs a ton of flavor,” says Grace. Sockeye stands up to super flavorful sauces, spice rubs, and marinades. Its firm, dense, and strikingly red flesh makes it a great choice for ceviche, gravlax, grilling, smoking, adding to chowders, and roasting in parchment.

Coho is roughly as lean (or fatty) as sockeye but has a more delicate flavor and firm but silky texture. Grace suggests, “It’s a great choice for gravlax, ceviche, and other raw preparations and excellent poached, smoked, grilled, cedar-planked, or pan-seared.”

King, with its rich fat-marbled flesh (4 times fattier than keta), buttery flavor, and soft, silky texture, reigns supreme in the salmon world. It makes great sushi, gravlax, ceviche, or any of the other raw preparations. Grilled, pan-seared, butter-basted, cedar-planked, and slow-roasted are also great options for showcasing king’s large luscious flakes. “Just err on the side of cooking to medium-rare to enjoy it at its best,” Grace suggests.

We’ve waited all year for the return of salmon to our docks and boxes. So whether you prepare a platter of sashimi or bake your salmon with an array of spices, consider each species a gift of the special interplay between ocean and river habitats that will continue for generations to come thanks to the efforts of Alaska’s fishing communities to defend salmon habitat. With your support, we are investing in a future for wild salmon and the communities who rely on them. Stay wild!