Big Fish

Americans purchase a billion pounds of tuna every year, yet few know where their tuna came from and how they were caught.

With this in mind, I called up Tom Fulkerson, a fisherman from Eureka, California, to get a better idea of what it’s really like to fish for North Pacific albacore off the coast of the United States. We connect through a mutual friend in mid-October when the albacore season is just wrapping up. Tom's driving home when I catch him on his cell phone.

Tom has been fishing for around 40 years. The first 20 years of his career he spent crabbing and fishing for salmon, but by the time he turned forty salmon fishing had begun disappearing in the management zone where he fished in California. So, the second half of his career has been spent chasing albacore tuna across the Pacific Northwest.

The shift prompted Tom to buy a bigger boat — a 58-foot wooden troller built in Astoria, Oregon, back in 1954. Shifting into a new fishery can be extremely costly. The overhead of gear and boat maintenance combined with the crapshoot that is fishing weighs on many captains. (One fisherman once told me that he would often lie awake at night thinking about the $100,000 of crab pot gear that was sitting on the bottom of the ocean.)

Tom says that the easiest part of being a small-boat owner and operator is actually catching the fish — it’s everything else that makes it hard. “I was telling somebody just today that after working on the boat for a month getting it ready and being stressed out about money, it seems like all the stress goes away once you head out onto the ocean and start a trip. It’s more like going on vacation than working at that point.”

One of the reasons Tom especially enjoys albacore fishing is because he can blast-freeze the fish at sea, allowing him to stay out and keep catching fish longer. That means that instead of a five-day salmon trip, he can go out for fifteen to twenty days. “We can stay out and just concentrate on fishing and get away from the stress.”

Freezing the albacore at sea also cuts down on the rush to get the fish back to the processor and into the freezer. This is especially handy since fishing on the open ocean means that offloading fish to a tenderboat isn’t possible. “I can't even imagine banging up against a boat trying to unload. We don’t get nice, cushy weather along the coast. A lot of the time I’d sign a contract for 15 to 20 knots, but we wind up getting a lot of 25 to 30 knots. It can last for weeks and weeks.”

He can’t see my raised eyebrows over the phone. “I don't know if that sounds like a vacation to me.”

Tom laughs, “Well, down here when the wind blows it just depends on how hungry you are. Everybody stays and fishes even though we’re getting beat up . . . even a handful is better than nothing.”

Catching tuna sustainably

When I ask him what it's like to catch an albacore Tom tells me there are a few methods. One of them is simply pole fishing for tuna — catching each individual albacore with a hand-held pole much like you would for sport only more extreme. He says fishermen fling the fish up on deck one after the next — each silver and white fish swimming so quickly that when they fly out of the water and land on deck, the sound of their tails fluttering against the boards sounds like rattles that build and build until the whole boat is vibrating with fish.

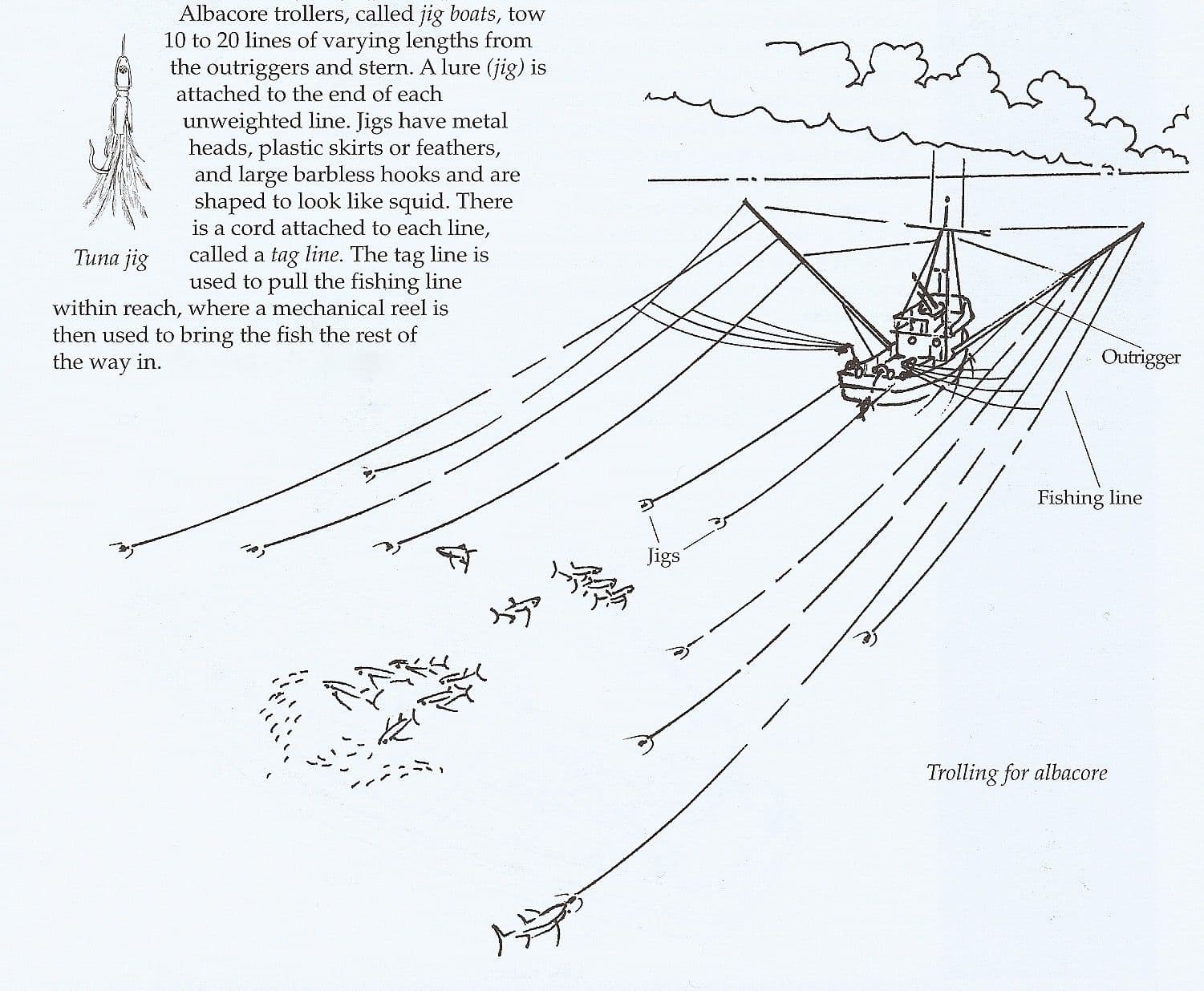

I admit that I thought this would be an exaggeration until I went on YouTube and proceeded to watch over an hour of albacore pole-fishing videos (parents be warned: this video contains salty language). Truly, they’re amazing to watch and I can confirm that it’s no fish story: pole-and-line fishermen flick their hooks in and out of the surface of the water, plucking fish after fish from the ocean and onto their back deck. They make it look easy. Although, when I eventually called Tom back he said that repeatedly bending forward and snapping back is actually pretty hard on the fisherman’s back. That’s why he prefers to troll jig — a similar concept, but with more hooks in the water which are pulled behind the boat in a fashion similar to salmon trolling.

Both pole-and-line and jig trolling are preferred by sustainable sourcing experts such as Carrie Brownstein who advises Whole Foods on their seafood quality standards. Both of these gear types require the fisherman to catch tuna one fish at a time, which minimizes bycatch. And since each fish is individually handled, it ultimately yields a very high-quality product.

Can vs loin?

An albacore’s body temperature is around 80 degrees, depending on the water temperature (a fact that I find astonishing and likely would have disputed on the phone with Tom if I hadn’t already been so humbled by the pole-and-line video). Fishermen submerge albacore into cold water on deck to bleed the fish and lower their body temperature before blast freezing them.

The quality of the final product is also determined by the sourcing and handling standards of the processor, so I reached out to Andrew Bornstein, the owner of Bornstein Seafoods where Sitka Seafood Market sources their albacore, to understand what his company is doing to ensure that their albacore maintains top flavor and texture.

When I ask him about what’s particular about their albacore he tells me that their fish are richly flavorful, “Fat equals flavor when it comes to fish!” says Andrew. It turns out that the North Pacific albacore has the highest fat content of any albacore in the world, largely due to their diet which is heavy in other nutrient-rich, fat-dense fish like sardines, anchovies, and herring.

Beyond that, Andrew says that they have the best albacore because they only work with the best boats — boats that bleed their fish well and freeze their fish until they’re ultra-cold.

Jake Knutzen, Borstein Seafoods’ program sales manager, explains that they test the core temperature of the fish as soon as the boat arrives at the dock and prior to purchase. The target temperature range is zero to negative ten degrees. “If we see fish that’s higher, like ten to fifteen degrees at core temp, we stay away from those vessels,” says Knutzen.

These seem like pretty stringent standards. I ask why these ultra-cold temps can make or break a buying decision. He explains that it has to do with that same high fat content that gives the North Pacific albacore such great flavor. It also means that fishermen and processors have to get the fish “as cold as you can as quickly as you can” in order to stop something called “oil migration.”

Oil migration? I give it a Google. After poking around and reading a few articles, I find out that oil migration is actually something I’ve seen in food products, and you likely have encountered it as well. Have you ever noticed a white, almost dusty-looking coating on an almond-filled chocolate bar? Apparently, this is called a “fat bloom” and it usually happens due to mishandling which allows the chocolate to get too warm.

That’s why Bornstein’s team is so vigilant about making sure that fish are kept super cold. “We do quality checks, testing the fish’s core temps, checking the bleeding as well as bloom to make sure the fish was bled correctly before it was frozen,” says Jake. Andrew agrees by telling me that if a boat doesn’t bleed its fish or if it doesn’t have the refrigeration to get its fish super chilled, that fish winds up being canned. In fact, he says that 75% of all the tuna caught on the west coast is canned. “It’s only the best 25% of the catch that is of sushi grade that we will buy and put up as a premium loin.”

75% of all the tuna caught on the west coast is canned.

What’s more, Borstein has the technology to cut those frozen-at-sea albacore into loins while they’re still frozen so that when they reach the doorsteps of Sitka Seafood Market’s members they’ve never been thawed.

Bornstein’s fleet is made up of men and women from coastal towns along the West Coast, ranging from as far south as California — like Tom — and all the way up the coast to Bellingham, Washington. Andrew says, “We have guys from Southern California we only see once a year, and then we have guys from Astoria, Oregon, whose kids play on our kids’ sports teams and we see them every day.”

Andrew describes the culture of the North Pacific albacore fleet as being comprised of family businesses.

“Many of the captains you meet today will tell you that they learned the craft from their grandparents and parents, and it has a certain amount of sentimental nostalgia for them.”

This seems fitting since Andrew Bornstein himself is the third-generation owner of the Bornstein family business and continues to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather along with his two brothers Kyle and Colin.

Across the North Pacific coast fishermen like Tom work year-round to deliver quality seafood to processors like Andrew who take great pride in preserving that frozen-at-sea fresh flavor. We hope that you enjoy your dinner all the more knowing the hard-working people who caught and processed your seafood.